|

Port

and navigation

The port represented an area of great economic dynamism and

cultural liveliness. Often, for reasons of defence, the cities

were not built on the coast but slightly inland. It was thus

that the most important cities had ports, for example Pyrgi

for Caere, which developed to the extent of becoming themselves

well-known and important centres. The ports, in addition to

receiving commercial and military traffic, were the gathering

point for a numerous fleet of small boats used by fishermen,

as the waters of the Etruscan coast were famous for the abundance

of fish to be caught there. In the first phase of their history,

the Etruscans were a sea-faring people respected in the whole

of the Mediterranean. Due to the lack of instrumentation and

the fragility of the vessels, which could not withstand storms,

navigation was as close as possible to the coast and only

during the day. At night, the cargo boats cast their anchors

in sheltered places, whilst the war galleys were hauled by

their crews on to the shore. The sailors of the period used

the stars and their knowledge of the conformation of the coasts

to guide them. Portolanos did exist but they were not commonly

used.

Maritime

trade

In ancient times, navigation represented the least costly

and safest method for the transport of goods and people. The

seas and navigable rivers were constantly plied by vessels

carrying every type of goods. As early as the 7th and 8th

centuries BC, the Etruscan merchants reached every part of

the Mediterranean in their ships. The typical products exported

were ceramics, in particular bucchero ware, and wine. The

cargo ships were squat and pot-bellied, with the keel at times

covered by a sheet of lead; the poop was high and curved,

the sail was square and attached to the central mast. They

used anchors of stone, and the ancients attributed their invention

to the Etruscans. To steer the boat, the helmsman used two

oars on the quarter-deck.

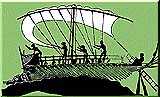

War

at sea

The warships, long and streamlined, moved forward by the force

of oarsmen in one or two rows and the wind was used as an

auxiliary driving force. The war galleys could be up to thirty

metres in length and in the most ancient times they had no

bridge; later, they had an upper bridge for the sailors and

soldiers. A rostrum was inserted on the prow which skimmed

the surface of the water. This was used in fighting to ram

enemy galleys. At sea, the combat technique was that of manoeuvres

and ramming. Success therefore depended on the skill of the

crews and the strength of the oarsmen. When the vessels came

close together, there was a heavy launching of projectiles,

at times in flames; when the ships were side by side, the

crews tried to strike one another using long lances. There

was boarding and hand to hand fighting when contingents of

foot soldiers were on board and when the aim was to capture

an enemy ship and its cargo. During the winter, naval operations

were suspended, but the disaster of entire fleets destroyed

by a storm was not infrequent.

|